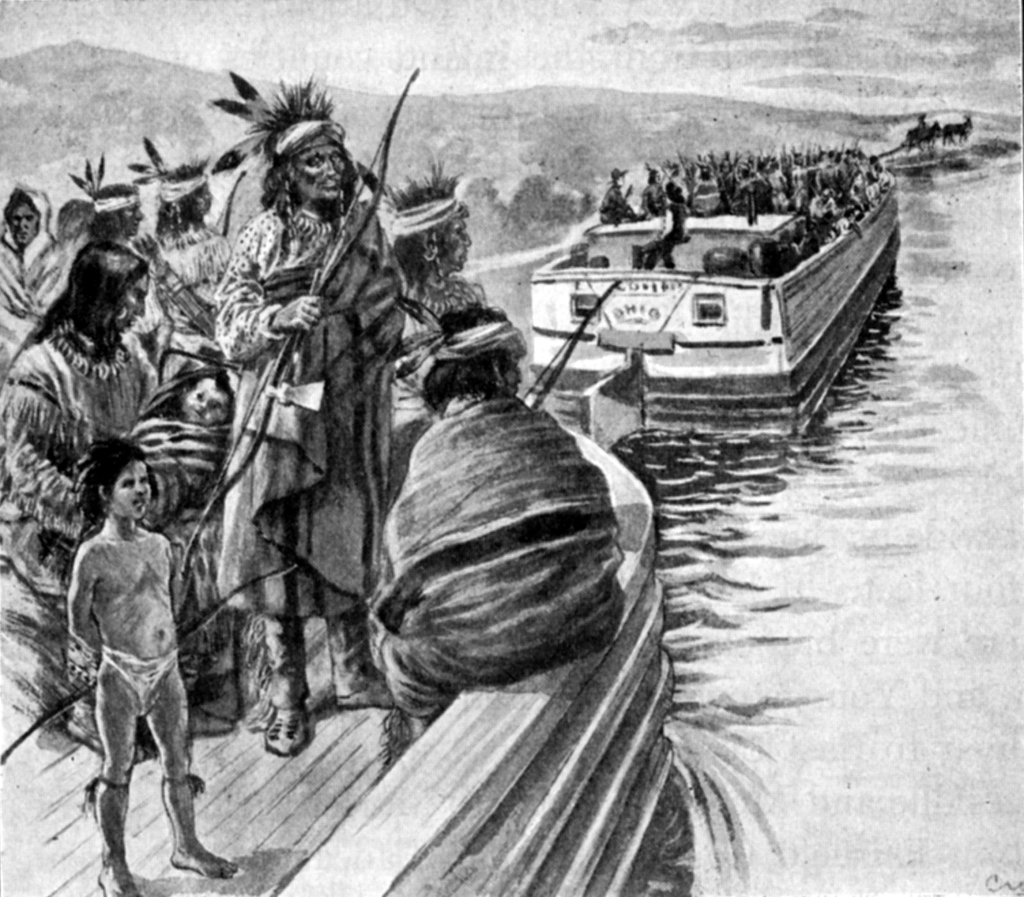

Wyandots in Ohio Image courtesy of the Wyandot County Historical Society. Original painting on display at the Wyandot County Museum, Upper Sandusky, Ohio

235 years ago, the American government began experimenting with new land policies, vowing to never displace Indigenous tribes without their consent. Ohio became the testing ground—and one of the first sites of empty promises that would remove the people who had long called this land home.

American expansion is etched into the landscape of northwest Ohio. A grid of county roads in one-mile intervals form perfect 640-acre squares across Ohio’s grasslands. Surveyors with measuring tapes cut squares across the United States, turning prairies, mountains and tribal homes into salable sections of public domain.

This is the legacy of American land policy.

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 turned the Midwest into a lab for a number of American expansion experiments, from the formation of new states to how the federal government disposed of the public domain. Ohio was the first testing ground.

American land policy is predicated on Indigenous dispossession. In the early-nineteenth century, there were six prominent tribes in Ohio, including the Wyandot, that claimed an expansive swath of Northern Ohio. The Northwest Ordinance stipulated that tribes in the region be treated with “the utmost good faith,” that “their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent” and that “in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed.” The United States broke these promises in less than a decade.

After years of regional conflict over contested lands, Indigenous leaders from 12 different nations signed the Treaty of Greenville (1795) that drew a line from the mouth of the Cuyahoga River across the state, reserving the northern portion as Indian lands. This was only the beginning of the dispossession of the Wyandot. White settlers continued to move into tribal territories as Wyandot leaders begged President James Madison to uphold the treaty.

“Listen!” the Wyandot leaders wrote. “We the Wyandots … peaceably have cultivated the land we have lived on, time immemorial, and out of which we sprung: for we love this land, as it covers the bones of our ancestors.”

Their words fell on deaf ears. After the negotiation of the Treaty of Maumee Rapids (Fort Meigs) in 1817, what remained of Wyandot lands centered around Upper Sandusky on the Grand Reserve.

The passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830 legalized what white settlers had been doing all along: it empowered and emboldened states to remove entire nations from their rightful homelands through physical and cultural violence. Ohioans set their sights on the fertile lands of the Grand Reserve where the Wyandot spent decades establishing houses, churches, farms and legible evidence that they made good neighbors. They had even planted robust orchards, investing in the livelihood of their future generations.

In 1843, after decades of active Wyandot resistance and political maneuvering, the State of Ohio succeeded in negotiating the tribe’s removal. In a final speech at the Wyandot mission in Upper Sandusky, Chief Squire Grey Eyes mourned his people’s departure.

“Here our dead are buried,” he said. “We have placed fresh flowers upon their graves for the last time. No longer shall we visit them. Soon they shall be forgotten, for the forward march of the strong white man will not turn aside for the Indian Graves.”

Two days later, on July 11, they packed up all of their worldly possessions and began a 150-mile, arduous trek from Upper Sandusky to Cincinnati to board steamboats—the Republic and the Nodaway—headed for present-day Kansas City. The weeklong walk to Cincinnati was made more difficult by whiskey peddlers who stalked the camps. There were three deaths, including an elderly woman and an infant. The captains of the Nodaway and Republic were not very accommodating, even pulling up the carpets so the passengers wouldn’t get them dirty. Once, for no apparent reason at all, the captain of the Nodaway made everyone disembark and spend a chilly night without shelter in a field outside of Kansas City.

Ohioans responded to Wyandot removal with pity.

“This is the last remnant of the Indian tribes in Ohio,” a reporter for The Cincinnati Enquirer opined. “They are gone. Once powerful in number and in strength, they are now a melancholy fraction. The fate of the Red man is theirs.”

Pity, however, is not the same as remorse. Americans fervently believed in their own right to their newly declared territories and states. Newspapers across the country announced the opening of Wyandot Country as a lucrative land opportunity. White families moved into empty homes and working farms, literally profiting off the fruits of Wyandot labor.

The Wyandot slowly started rebuilding their lives in Kansas on land they purchased from the Lenape. In 1855, the federal government dissolved the Wyandot’s tribal status and—without their consent—made them citizens of the United States. Under protest, a portion of the tribe moved to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma to live their lives under their own sovereignty. The Wyandot successfully petitioned for reinstatement of their tribal status in 1867, and the Wyandotte Nation is still headquartered in Oklahoma. But the formation of the United States left fractured nations scattered in its wake. Today, Wyandot bands are located in Ontario, Michigan, Kansas and Oklahoma.

The Northwest Ordinance established one of America’s longest lasting and most impactful land policies. It’s important to remember that these policies necessitated the removal of Indigenous people. But Ohio’s remembrance of its first people is incomplete. More work is required to reconcile the present with the past, understand Ohio’s cultural landscape and begin healing the intergenerational trauma American expansion caused Indigenous nations.

Rebecca Wingo, PhD is a scholar, author and the Director of Public History at the University of Cincinnati. Broadly, she studies houses—from Indigenous homes to the use of eminent domain to displace Black citizens for highway construction in the 1950s and 1960s.

For more about the Wyandot and the removal of Midwest tribes, consider these books:

- On the Back of a Turtle: A Narrative of the Huron-Wyandot People by Lloyd E. Divine, Jr.

- Land Too Good for Indians: Northern Indian Removal by John P. Bowes

- Winning the West with Words: Language and Conquest in the Lower Great Lakes by James Joseph Buss

- The Other Trail of Tears: The Removal of the Ohio Indians by Mary Stockwell