By Rebecca Brown Asmo

I have a confession to make. Until 2020, I didn’t really know what the humanities were.

Yes, that’s correct. I’m the leader of our state’s humanities council, the “boots on the ground” in Ohio for the National Endowment for the Humanities and I didn’t really know what the humanities were until three years ago.

I realize that this confession is likely a risky one given the fact that so many of you reading this message have dedicated your lives to the pursuit of these disciplines.

I am also keenly aware of the many ways that the humanities are under attack in American institutions today.

But my hope is to offer a fresh perspective on how to approach the humanities—one that shifts us from being constantly on the defensive to evangelists for the ways the humanities are thriving in public life.

The humanities positively impact the lives of everyday people in monumental and transformational ways, but too many of us have no language to talk about this.

As a result, the stories about how the humanities transform lives fade into the background, leaving an increasingly small and under-resourced group of academics, scholars, and institutional leaders to advocate for the humanities in the ongoing “debate” about their value.

We must become better storytellers about the incredible impact the humanities have on our individual lives, on the people we care about and on our communities. Not in nebulous terms but in detailed, human centered and specific ways that will change hearts, minds, policy and funding.

I started off with the shocking claim that I didn’t really know what the humanities were until three years ago. While that is true in a literal sense, I have had a deep relationship with the humanities since my earliest moments in this world. But I only recently found the language to describe it that way.

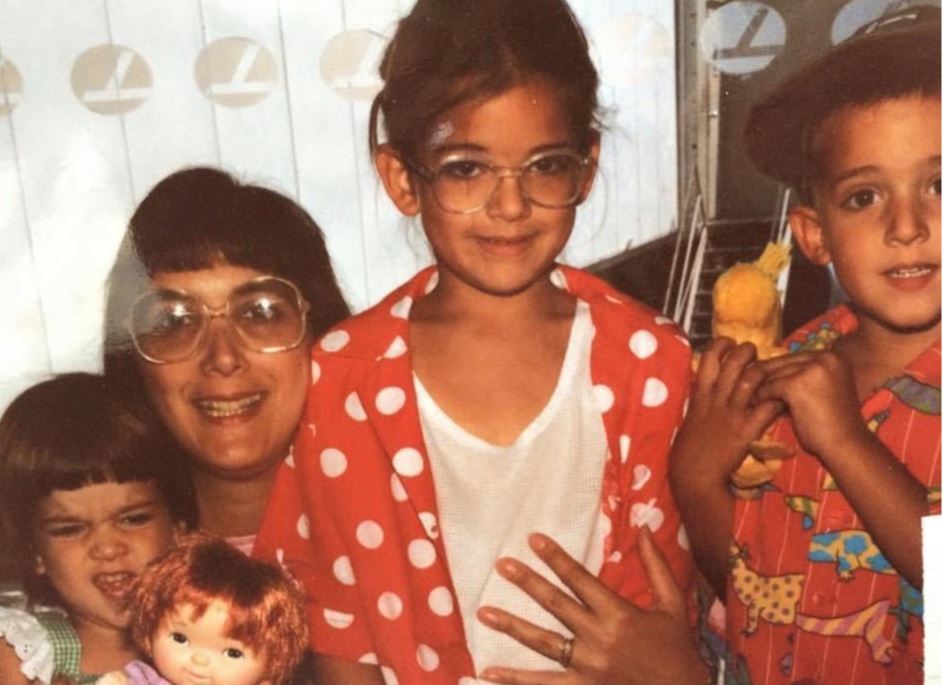

I grew up in a household that was often chaotic. My brother has autism and schizoaffective disorder. My parents are wonderful people, but they had three kids (one who needed a lot of support), they both worked full time, and my mother was also a dedicated disability rights activist on top of her job.

This meant that my parents were often overwhelmed and unavailable for us. My brother’s disability and mental health diagnoses, which weren’t as well understood in the 1980s and early 1990s as they are today, meant that he was often volatile, violent, and ostracized by much of our broader community—who ostracized the rest of our family too.

Despite these difficulties, the greatest gift my parents gave me was a deep appreciation for reading, museums, newspapers, geography, and nature. I escaped into books. Lois Lowry, the Boxcar Children, American Girl Doll stories—I loved anything that involved history because I could imagine being transported to another place and time.

In middle school I started walking to my local Crown Books to buy a new Danielle Steel book every few days. I loved the ones that were set in the past like San Francisco during the gold rush, or World War II.

To my parents’ credit they always said to me, we don’t care what you read as long as you are reading.

As I grew into my teens, I discovered a love for coming-of-age stories like A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and A Separate Peace, and a near obsession with dystopian novels by Margaret Atwood, Upton Sinclair, and Aldous Huxley.

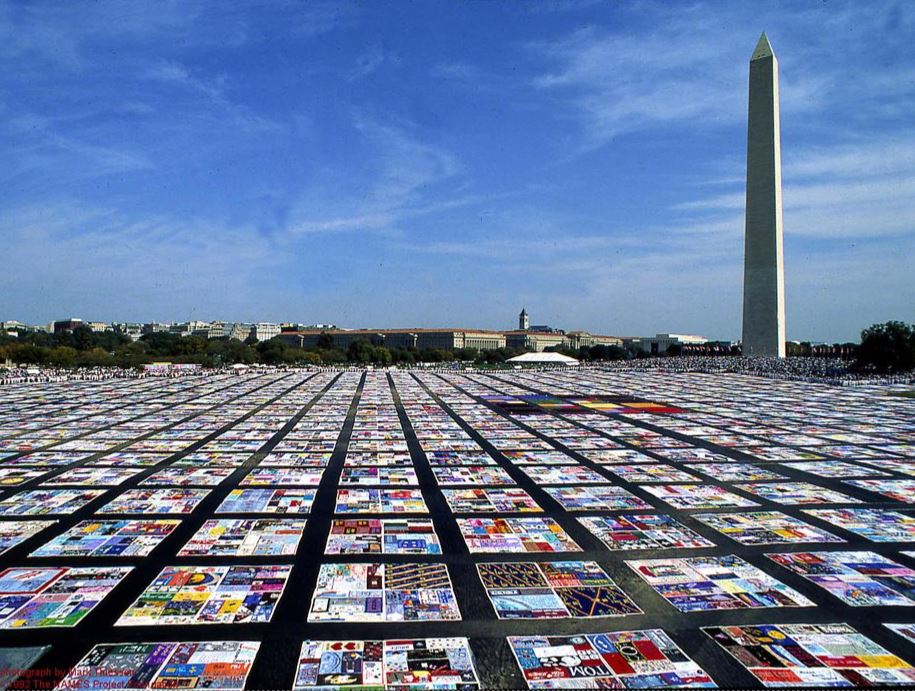

At fourteen, my parents let me take the Metro to Smithsonian museums—which is kind of surprising since they were very strict. I took full advantage of this and regularly took the Orange line from Vienna, Virginia, where we lived, to the Smithsonian to visit the National Gallery of Art, the Museum of American History, and the AIDS Memorial Quilt when it was displayed on the National Mall.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but the humanities were a forcefield protecting me from the difficulties of my day-to-day life at home.

When I was reading, or imagining what it would be like to live in a different time in history, or exploring a museum, I didn’t have to think about home, which was miserable a lot of days or school which was a social minefield for a teen girl in the early 1990s who just wanted to be accepted. But I had no language to talk about this.

When I got to college, I had no idea what I wanted to study. I took an art history class and instantly knew that is what I wanted to spend the rest of my time at Georgetown studying. I loved talking about history through the lens of artists, their patrons, and the people and scenes they painted. It was full of gossip and palace intrigue.

I loved the seminars where we talked for hours about subjects ranging from feminism to esoterism. I had all the museums in Washington, DC, at my disposal, which led to incredible experiences. I got to handle rare Medieval prints in Georgetown’s archives, explore collections storage at the American History Museum, and take an oral history exam about Dutch painting in the Rembrandt gallery at the National Gallery of Art.

When I was talking about art, writing about art, or quietly exploring a museum, I didn’t have to think about things like my body, or the eating disorder that was shrinking it away, or what boys thought of me, or if I was smart enough to be at Georgetown. I felt competent and at home.

Again, the humanities were a forcefield protecting me, but I had no language to talk about this because not even my professors at Georgetown talked to me about the humanities.

After college, I spent a few years working in museums in Washington, DC, and, eventually, in Columbus, Ohio. I found my way into fundraising roles, which I ended up being pretty good at, but was not something anyone had ever told me was a career prospect with a humanities degree.

Eventually, my experience in fundraising led me to the Boys & Girls Clubs of Central Ohio. The 10 years that I served as its CEO were formative career and life experiences.

In 2020, I had what many people would call a midlife crisis, but what I call a midlife awakening. The humanities helped me find my way back to who I had always been, to healing, to a life that is better and freer than I ever imagined. Again, the humanities were my forcefield. Again, I had no language to talk about this.

Then, in 2021, I interviewed for and ultimately accepted the position of Executive Director of Ohio Humanities, and I finally found the language to talk about all the ways that I knew personally, professionally, and as a leader in my community that the humanities could transform.

Every day in this job, I have the opportunity to see the ways in which the humanities are thriving in the public sphere.

To give but one example: In December 2021, a Columbus-based organization called “We Amplify Voices” launched a project called “Life Stories” inside the Ohio Reformatory for Women. Life Stories worked with fifteen women serving long and life sentences. The women worked as part of two groups—the storytellers and the media crew. Over a six-month period, the women worked with Professor Michal Raizen and award-winning documentary filmmaker Nicolette Swift to conduct and record oral histories to document the stories of their incarcerated sisters. Together, these women created a series of documentary shorts about the lives of women serving long and life sentences along with an art installation that conveyed what life is like in prison.

Today, this installation and the documentaries are touring sites around Ohio.

The stories these women curated and documented offer a unique glimpse into the lives of women who are often disregarded. They talk about their childhoods, their families, their crimes, the challenges of life in prison, but also their hopes for the future. Life Stories participants speak with pride about how this project has provided a service, not only to their incarcerated sisters, but also to people like you and me who walk away from Life Stories seeing incarcerated women in their full humanity—something we don’t often take time to reflect on.

One participant said about the project, “Life Stories taught me what it looks like when you love yourself.”

The humanities bring a sense of belonging, purpose, and understanding to systems that are designed to rob us of humanity.

In Ohio, less than 30% of adults have a bachelor’s degree or higher. So when we spend our time lamenting the downfall of the English major, we’ve already lost two-thirds of people who most definitely value the humanities but just don’t have the language to express that.

This does not mean that we ignore what are clear attacks on humanist thinking and scholarship. The humanities projects that Ohio Humanities supports would not happen without humanities teachers, scholars, research and funding.

We must, however, be proactive in leading conversations and advocacy that go beyond the walls of institutions. We must bring people into the humanities who don’t believe they belong here, and we must give them language to talk about the shared human experience that the humanities give us.

Ohio Humanities is committed to being a partner and a leader as we work together to define and amplify a public humanities sector. We have redefined how we talk about the humanities, centering people and their stories over disciplines.

And for the first time in our 50-year history, we are advocating state and local government and building a philanthropic infrastructure so we can work towards funding parity with the public art sector and pass this funding onto public institutions who are bringing the humanities to life in communities across Ohio. This is going to take time, and it’s going to be very difficult—especially given the dynamics at play in American society today—but this effort is critically important for our future.

The humanities aren’t just a list of subjects and majors. They are our north star. For me, no light has shown brighter as I navigate my way through life.

I hope you will take stock of the stories you have. The ways in which the humanities weave their way through our lives in both obvious and subtle ways. I hope you will share these stories, spark conversations, and inspire ideas for a future where everyone’s unique stories are heard and valued.